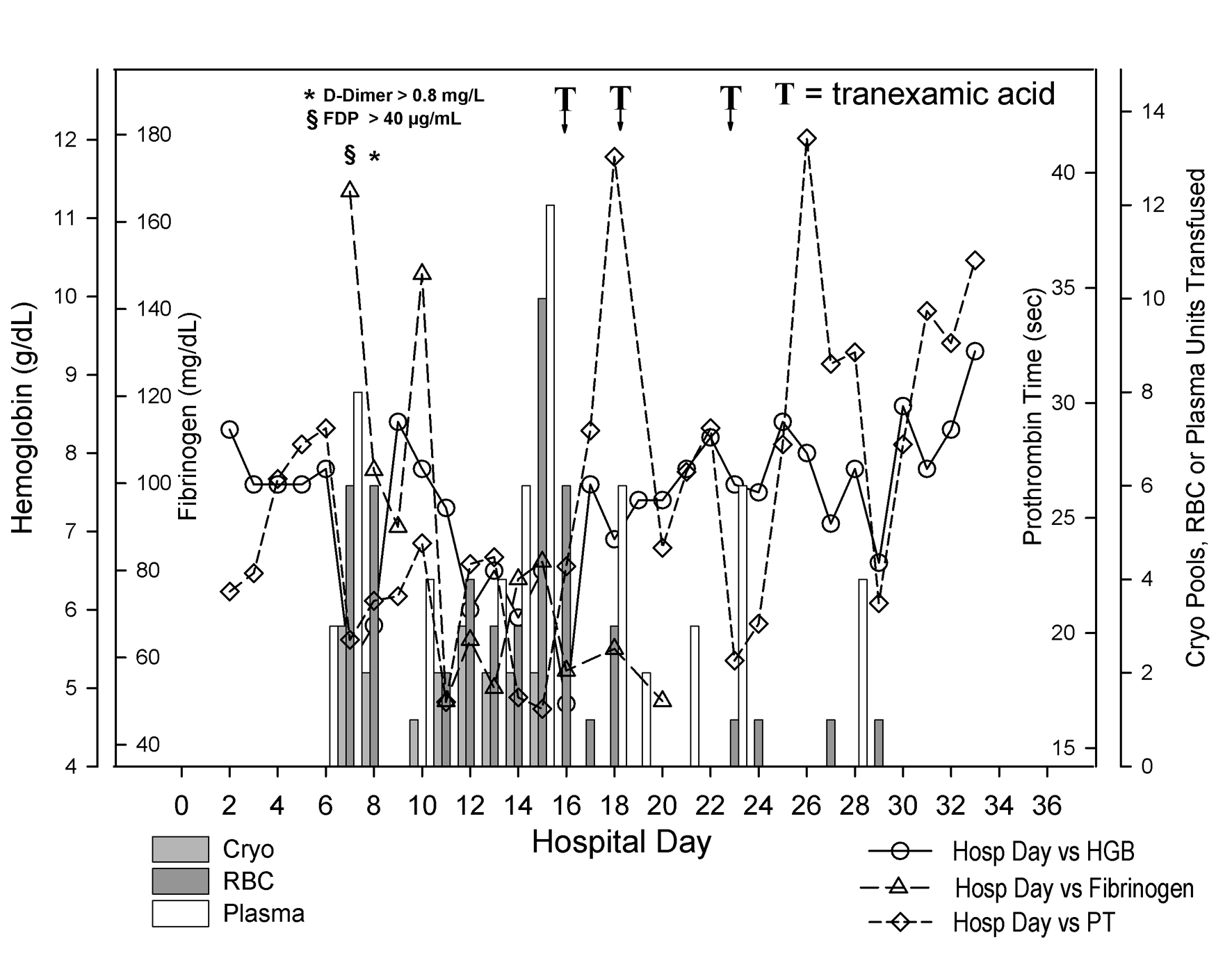

Figure 1. Coagulation status and blood product use during hospitalization. Day of hospitalization is depicted on the X-axis. Separate Y-axes depict hemoglobin (g/dL, open circles), fibrinogen (mg/dL, open triangles), prothrombin time (sec, open diamonds) and pooled cryoprecipitate (Cryo, 5 units per pool, light gray bars), units of red blood cells (RBC, dark gray bars), and units of plasma (white bars) transfused to the patient. The patient’s hemoglobin fell precipitously between hospital days 6 and 7. The fibrinogen began to fall as well. As shown at the top left of the figure, fibrin degradation products and D-dimers were found markedly elevated on hospital day 7 and 8 respectively. Between hospital day 6 and 14, he received 24 units of packed red blood cells, 25 units of plasma and 15 pools of cryoprecipitate. Although not shown on the figure, he also received 13 apheresis platelets during that interval. He received another 16 units of packed red blood cells between hospital day 15 and 16. He then received tranexamic acid on two occasions (the first one in the evening of day 15 through early morning of day 16 and the second one in the afternoon of day 18). After the second dose, his hemoglobin remained stable with the administration of only 4 units of packed red cells beginning with hospital day 19. Despite the persistence of a prolonged prothrombin time, he appeared to have stopped bleeding.