| Journal of Hematology, ISSN 1927-1212 print, 1927-1220 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Hematol and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.thejh.org |

Case Report

Volume 6, Number 4, October 2017, pages 87-89

Methemoglobinemia: A Rare Entity Caused by Commonly Used Topical Anesthetic Agents, a Case Report

Prashanth Rawlaa, c, Jeffrey Pradeep Rajb

aDepartment of Internal Medicine, Monmouth Medical Center, Long Branch, NJ, USA

bDepartment of Pharmacology, St John’s Medical College, Bangalore, India

cCorresponding Author: Prashanth Rawla, Department of Internal Medicine, Monmouth Medical Center, Long Branch, NJ, USA

Manuscript submitted April 25, 2017, accepted May 19, 2017

Short title: Methemoglobinemia

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jh325w

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Benzocaine, a topical anesthetic agent, is widely used during short procedures like endoscopy, endotracheal intubation and likewise. Here we report a case of benzocaine spray-induced methemoglobinemia in an adult male patient during the transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) presenting as hypoxia and improved subsequently in the next 2 h on low-dose intravenous methylene blue. Causality assessment of the adverse event was probable, and preventability assessment was unpreventable. The patient was discharged with no further complications at good health. A relevant etiopathology and managing principles are summarized in this case report such that it serves as an awareness to all medical fraternity about this unexpected yet life-threatening adverse drug reaction to an otherwise safe local anesthetic.

Keywords: Methemoglobinemia; Benzocaine; Topical anesthetics

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Benzocaine is a local anesthetic which is produced by the esterification of para-amino-butyric-acid with ethanol. It is widely used as a topical anesthetic agent for pain relief in oral sores, sore throat, and baby teething gels. They are available as over the counter suppositories and gels to treat pruritus and pain of the vagina and anal canal [1]. Benzocaine relieves the pain stimulated at free nerve endings by blocking the voltage-dependent sodium channels (VDSCs) on the neuron membrane thereby stopping the propagation of the action potential which is otherwise perceived by the central nervous system as pain. It has very low solubility and therefore a longer duration of action [1].

Here we report a case of methemoglobinemia in an adult man that occurred secondary to the use of topical benzocaine for transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) and also discuss the relevant pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and medical management. Though benzocaine-induced methemoglobin is a rare but well-reported adverse event [2], our objective here is to increase further awareness as this is a life-threatening complication secondary to an otherwise safe local anesthetic that is not even administered systemically but topically.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

A 44-year-old gentleman came to the emergency room (ER) with complaints of weakness and physical deconditioning for 2 days. He is a diagnosed patient of type I diabetes mellitus, peptic ulcer disease, depression, seizure disorder, Charcot foot of the left foot and a mild developmental delay. The patient was prescribed insulin detemir, escitalopram, depakote, clonazepam, gabapentin, levetiracetam, lisinopril and finasteride for his various co-morbidities. He gave a history of non-compliance to medications and also a history of previous hospital admissions for diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA). He was also diagnosed with substance abuse with tobacco with seven pack-years of smoking in the last 15 years. He also consumes alcohol five units per week and occasional use of marijuana for the past 15 years.

In the ER, the patient was diagnosed to have DKA and acute kidney injury (AKI) secondary to drug-induced acute tubular necrosis (ATN) along with dehydration and hyperkalemia. Therefore, he was treated with intravenous (IV) fluids and an insulin infusion and his DKA resolved.

As a routine workup to rule out the exacerbating factors of DKA, a blood culture was done which came positive for methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA). He was initially started on vancomycin and renal adjusted dose of piperacillin/tazobactam. However, due to persistent positive blood cultures with MSSA, he was taken up for further evaluation. Meanwhile, the patient had a chronic fracture of his left humerus proximally with a non-union for 1 year. An orthopedic consultation was sought for as his range of movements was limited. A computerized tomography (CT) scan of the upper extremity was performed which confirmed the non-union and also reported osteomyelitis. Large septated fluid collections in the subcutaneous soft tissues and muscles of the shoulder and the entire left arm suggesting seromas related to old hemorrhage were also reported in the CT. However, since radiologically an infection could not be ruled out, an incision and drainage was done and drains were placed. The culture of the fluid drained also grew MSSA.

As the patient had septicemia and a localized abscess, a cardiac transthoracic echo was done to rule out vegetations on the heart valves. He was further subjected to TEE which was performed by the cardiologist who confirmed the absence of any vegetations. During the TEE benzocaine and lidocaine were used as a topical anesthetic agent. During the entire procedure, the patient had persistent hypoxemia with his oxygen saturation staying between 85% and 87% on 100% non-rebreather mask. An arterial blood gas revealed pH 7.43, PCO2 41, PO2 249, and oxygen saturation 85%. He did not show any signs of cyanosis. The arterial blood color was not noted. Chest X-ray was done and showed no abnormalities. CT angiogram of the chest was gone which showed no evidence of pulmonary embolism. A probable diagnosis of methemoglobinemia was considered. Methemoglobin level checked using co-oximetry during the procedure was 28.6% initially. He was treated with one dose of methylene blue 2 mg/kg IV, and 2 h later his oxygen saturation was found to be maintaining at 92-94% on 2 L oxygen via nasal cannula. His repeat methemoglobin levels were 8.2%. Subsequently, his hypoxia got better, and he maintained good saturation after that on room air. His repeat blood cultures sent 2 days after abscess draining and came back negative. His medical condition improved and he was discharged on IV antibiotics to a skilled nursing facility.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Methemoglobinemia is a clinical condition wherein there is an elevated amount of methemoglobin within the erythrocytes in the circulating blood. A normal hemoglobin has iron in the ferrous state while methemoglobin contains iron in the ferric state. Thus this compound is unable to bind and carry oxygen resulting in a state of functional anemia. Secondly, at the tissue level, it does not readily dissociate with the oxygen as the oxidized iron changes the heme tetramer, thus shifting the oxygen dissociation curve to the left as in alkalosis. The normal level of circulating methemoglobin in the blood is less than 1%. Having said that, there is an equilibrium between the production and breakdown of methemoglobin. The methemoglobin that is continuously formed in the red blood cells is reduced to deoxyhemoglobin by nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide-dependant (NADPH) methemoglobin reductase. This accounts for 95% of the reduction besides which there are other slow acting pathways like glutathione and ascorbic acid pathway [3].

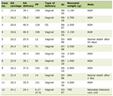

Methemoglobinemia can be either congenital or acquired, with the acquired form being more common. The congenital form is due to congenital absence of the reductase enzyme whereas, and pharmacological agents are the most common acquired causes of methemoglobinemia [4]. Some of the drugs which are most commonly implicated (Table 1) are nitrites, nitrates, inhaled nitric oxide, nitroprusside, silver sulfadiazine, dapsone, sulfonamides, antimalarials (chloroquine, primaquine), flutamide, metoclopramide, acetanilide, phenacetin, chlorates, pyridium, phenytoin, probenecid, chlorates, and phenazopyridine hydrochloride [5]. Our patient was not receiving any of the drugs mentioned above.

Click to view | Table 1. Most Common Drugs and Chemicals Causing Methemoglobinemia |

Clinically, methemoglobinemia is suspected where there is cyanosis out of proportion to respiratory distress. Also since methemoglobin is a dark pigment, it causes the blood to appear chocolate in color, so a dark arterial blood gas sample is corroborative [6]. The half-life of methemoglobin is 55 min, and hence the onset of symptoms is usually within 20 - 60 min [7]. Circulating levels of methemoglobin below 30% produce mild fatigue to no symptoms at all, whereas levels between 30% and 50% cause moderate depression of the cardiovascular and central nervous system. Levels above 60% can be lethal, and that above 70% are incompatible with life [8].

Once we suspected methemoglobinemia, our patient was administered IV methylene blue which is the drug of choice. The drug is a dye with antiseptic action along with dose-dependent oxidative or reductive properties. It is a reducing agent acting via the NADPH methemoglobin reductase pathway. Methylene blue when given in lower concentrations gets reduced in the erythrocytes and in tissues to form the leucomethylene blue. This active metabolite then causes reduction of methemoglobin to hemoglobin and converts the iron atom from ferric state to ferrous state, thereby restoring the oxygen carrying capacity of the hemoglobin [9]. The usual dose of methylene blue is 1 - 2 mg/kg of 1% solution IV over 5 min and a repeat dose after 1 h if hypoxia persists. Cyanosis resolves within 15 - 30 min, and 50% reduction in methemoglobin level is noted within 30 - 60 min. Caution must be exercised not give high doses as methylene blue can oxidize the ferrous ions to ferric ions and further deteriorate the condition [10].

According to the WHO causality assessment, benzocaine is the “probable” cause for methemoglobinemia as de-challenge was positive and re-challenge was not done. According to the Naranjo algorithm, the causality is again “probable” with a score of 8 [11]. According to the Schumock and Thornton preventability scale, the ADR is unpreventable [12] and based on the Hartwig and Siegel severity assessment scale, the severity of the reaction is placed at level 4 which involves withholding of the suspected drug and a prolonged hospital stay by at least 1 day with no admission in the intensive care unit [11].

Conclusion

Nosocomial benzocaine-induced methemoglobinemia is a rare but fatal complication, and a strong clinical suspicion is a common driver to look out for methemoglobinemia. This rare complication should be borne in mind and looked for especially in the smaller community-based setups while using local anesthetics especially benzocaine. The treatment should be initiated immediately with low-dose methylene blue dye IV which converts methemoglobin to normal hemoglobin thus enhancing the oxygen carrying capacity of the red blood cells. Since there have been reports citing topical benzocaine as a potential threat for methemoglobinemia, we recommend safer alternatives whenever possible. If recognized promptly this condition can be treatable and will help prevent unnecessary testing and morbidity and sometimes even mortality.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors do not have any conflicts of interest or financial relationships to disclose.

Author Contributions

Study design, drafting, critical revisions and final approval by PR and JPR.

| References | ▴Top |

- Rang HP, Ritter JM, Flower RJ, Henderson G. Rang & dales pharmacology, 8th ed. Elsevier Ltd. 2016; p. 530-535.

- Hoffman C, Abubakar H, Kalikiri P, Green M. Nosocomial methemoglobinemia resulting from self-administration of benzocaine spray. Case Rep Anesthesiol. 2015;2015:685304.

doi - Curry SC, Carlton MW. Hematological consequences of poisoning - methemoglobinemia. Clinical management of poisoning and drug overdose. In: Haddad LM, Shannon MW, Winchester JF (eds). Philadelphia, WB Saunders Co, 3rd Ed. 1998; p. 226-230.

- Rehman HU. Methemoglobinemia. West J Med. 2001;175(3):193-196.

doi pubmed - Griffin JP. Methemoglobinemia. Adverse Drug React Toxicol Rev. 1997;16:45-63.

pubmed - Ferraro-Borgida MJ, Mulhern SA, DeMeo MO, Bayer MJ. Methemoglobinemia from perineal application of an anesthetic cream. Ann Emerg Med. 1996;27(6):785-788.

doi - Coleman MD, Coleman NA. Drug-induced methemoglobinemia. Treatment issues. Drug Saf. 1996;14:394-405.

doi pubmed - Ellenhorn MJ. Ellenhorn's medical toxicology: diagnosis and treatment of human poisoning, 2nd ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1997. p. 1496-1499.

- Sass MD, Caruso CJ, Axelrod DR. Mechanism of the TPNH-linked reduction of methemoglobin by methylene blue. Clin Chim Acta. 1969;24(1):77-85.

doi - Posthumus MD, van Berkel W. Cytochrome b5 reductase deficiency, an uncommon cause of cyanosis. Neth J Med. 1994;44(4):136-140.

pubmed - Srinivasan R, Ramya G. Adverse Drug Reaction-Causality Assessment. Int J Res Pharm Chem. 2011;1(3):606-12.

- Schumock GT, Thornton JP. Focusing on the preventability of adverse drug reactions. Hosp Pharm. 1992;27(6):538.

pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Hematology is published by Elmer Press Inc.