| Journal of Hematology, ISSN 1927-1212 print, 1927-1220 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Hematol and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://www.thejh.org |

Case Report

Volume 13, Number 3, June 2024, pages 121-124

Recurrent Infection in a Young Female Patient Recently Diagnosed With Primary Evans Syndrome Without Neutropenia

Jennie Ana, b , Preye Amaruntowaa, Waleed Ahmeda, Ali Khana, Muhammad Shahzada

aSt. James School of Medicine, Anguilla, Park Ridge, IL 60068, USA

bCorresponding Author: Jennie An, St. James School of Medicine, Anguilla, Park Ridge, IL 60068, USA

Manuscript submitted March 19, 2024, accepted May 25, 2024, published online June 28, 2024

Short title: Primary Evans Syndrome Without Neutropenia

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jh1265

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Evans syndrome (ES) is a rare autoimmune condition of unknown etiology that occurs in a small subset of patients diagnosed, either sequentially or concomitantly, with immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) or warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA). Neutropenia is present occasionally. Diagnosis is based on exclusion with a median age of 52 years of age. Here we have a case of a young patient with ES presenting with recurrent infection. ES should be included in differential diagnoses for patients presenting with AIHA, ITP, cytopenias or recurrent infection as the prognosis is more favorable when diagnosis is made early and symptoms are still mild.

Keywords: Autoimmune cytopenia; Autoimmune hemolytic anemia; Coombs test; Immune thrombocytopenia; Immunoglobulins; Neutropenia; Thrombocytopenia

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Evans syndrome (ES) is a rare condition with no known genetic cause that involves the presence of either warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA), immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) [1-8], or both. Neutropenia may or may not be present. The etiology of ES can be primary idiopathic or secondary to other chronic autoimmune conditions, which makes it a diagnosis of exclusion. Due to the limited number of cases documented in the adult and pediatric populations and the lack of specificity in existing diagnostic tests, the recognition and expeditious identification of ES becomes difficult. Current techniques such as the interpretation of a complete blood count (CBC), a Coombs test, reticulocyte count and serum haptoglobin levels may be useful, but these values are not diagnostic of ES as they can be abnormal in numerous other pathologies. Oftentimes, diagnosis is made in the fifth or sixth decade of life when symptoms have already become debilitating. The low median survival rate and high risk of chronic complications associated with the delayed diagnosis of ES calls for further research pertaining to more efficient and specific diagnostic techniques [2].

In this case report, we present a 22-year-old Caucasian female with ES who was hospitalized multiple times in the past couple years and throughout her lifetime due to recurrent infection of varying etiology. Diagnosis of ES was not made until recently.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

Here is a case of a 22-year-old female Caucasian patient who presented with her third bout pneumonia in the past 2 years. Upon her arrival to the emergency department, symptoms consisted of a 4-day history of fever (ranging from 101 to 103.5 °F), night sweats and a productive cough with green sputum. The fever and night sweats caused her to wake up two times at night to change her clothes.

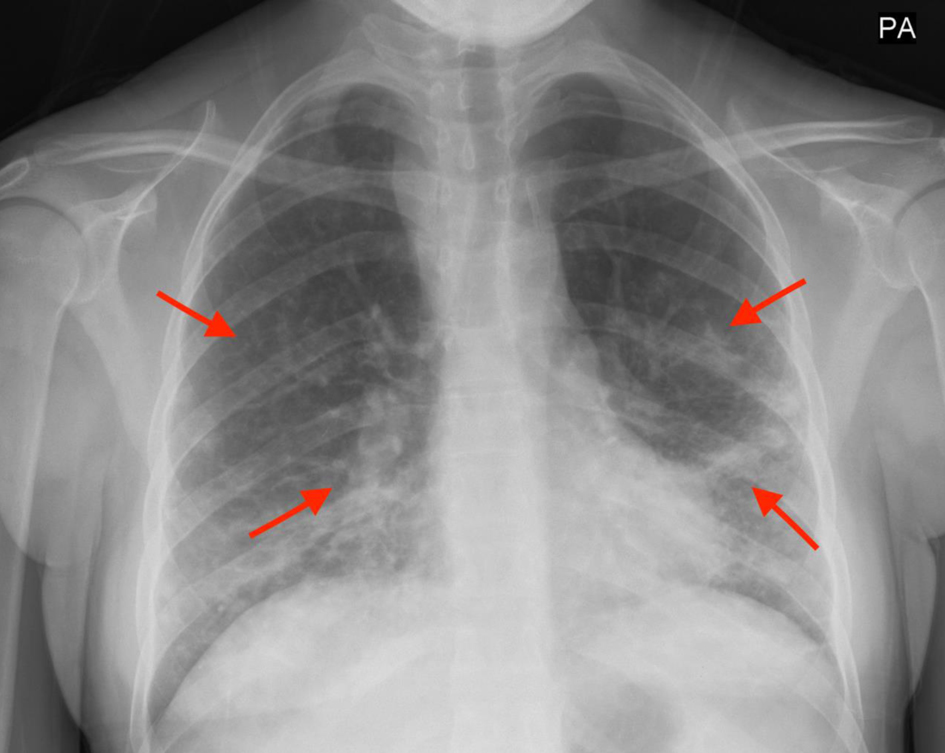

In Figures 1 and 2, X-rays revealed pneumonia, similar to 2 years prior, with increased densities along the middle to lower lung fields with patchy to reticular nodular density changes. These changes represent a component of acute pneumonitis superimposed upon chronic lung disease changes. Heart size was within normal limits and no splenomegaly or lymphadenopathy were noted. Nasal swab PCR test was positive for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), rhinovirus, and Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Cold agglutinins (IgM) were not detected.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Increased densities along the middle to lower lung fields with patchy to reticular nodular density changes (red arrows). |

Click for large image | Figure 2. Densities in the middle and lower lung fields (red arrows). |

Treatment initially included prednisone and azithromycin but was later switched to amoxicillin-clavulanic acid due to side effects including blurred vision, migraines, vomiting, and dizziness. Acetaminophen was used every 8 h to relieve fever. A non-productive cough persisted for several weeks despite completing the antibiotic regimen.

Her past medical history includes ES, shingles, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), and recurrent infection. Other infections in the past 2 years consist of the following: otitis interna complicated by facial palsy, otitis media requiring tube placement, and a mastoid infection requiring surgery. The unexplained nature of recurrent infections in a healthy young patient demanded further diagnostic workup for underlying cause. ES was diagnosed a year prior to her current emergency department visit.

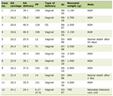

Our patient’s previous laboratory values obtained a year prior to admittance to the emergency department demonstrated hemolysis and subsequent anemia. This is illustrated in Table 1 which shows an elevated reticulocyte count and indirect bilirubin concurrently with a decreased haptoglobin count.

Click to view | Table 1. Lab Values Prior to Admittance to the Emergency Department During the Time of Diagnosis of Evans Syndrome |

A positive IgG Coombs test (direct antiglobulin test), ADAMTS13 assay of 62 IU/dL, and low C3/C4 complements were also noted. The presence of the ADAMTS13 titers allowed us to obviate thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) as a differential. Blood smears demonstrated schistocytes and megakaryocytes which suggested that the thrombocytopenia is likely immune-mediated. During the time of diagnosis, other infectious diseases (hepatitis B and C, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), etc.) and autoimmune causes (systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome (ALPS)) were ruled out via a CBC, titers and an antinuclear antibody (ANA) test. These findings along with clinical history of recurrent infections allowed for the diagnosis of ES with both AIHA and ITP. She is currently being treated with rituximab and is undergoing a trial of various immunosuppressants.

After the resolution of the recent pneumonia, the patient was discharged but returned to the emergency department a month later due to shortness of breath, cough, foul-smelling sputum and fever. Diagnostic workup concluded a 2.2 cm pulmonary abscess as a complication of pneumonia and required intubation. Clindamycin therapy was also initiated as sputum results were pending and prior to drainage of the abscess.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Etiology and pathophysiology

ES may be primary or secondary. Primary ES is often idiopathic, while secondary ES occurs in the presence of other autoimmune diseases. Drugs such as diclofenac and ramipril have been associated with drug-induced ES [3].

The exact pathophysiology of ES is unknown, thus often considered idiopathic. Like other autoimmune diseases, auto-antibodies are made against self-hematogenic cells: red blood cells (RBCs), platelets and white blood cells. This results in the characteristic conditions often seen in AIHA, ITP and rarely neutropenia. AIHA results from IgG against RBC surface antigen, with Fc interaction on cytotoxic cell surfaces, resulting in complete or partial phagocytosis [8]. Phagocytosis mainly occurs in the spleen. Incomplete phagocytosis results in spherocytes in the peripheral smear. ITP also results from IgG autoimmune antibodies against platelet derived glycoproteins, especially GP IIb/IIIa glycoprotein. Thus, hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia are evident, which may occur together or individually.

Presentation

The presentation of ES varies depending on the cells affected [5, 9-11]. In some patients, only one type of blood cell line may be affected whereas in others, multiple lines may be affected. In the case of warm AIHA, patients will exhibit features of hemolysis such as shortness of breath, dizziness, fatigue and palor [9, 12, 13]. In older patients, warm AIHA could lead to ischemic pathologies such as cerebral vascular disease and acute coronary syndrome. In patients with ITP, bleeding, easy bruising or even life-threatening hemorrhage could be present [8].

Diagnostic techniques and evaluation

For primary ES, the diagnostic techniques for warm AIHA, ITP and AIN vary. In the presence of anemia with lab values indicating hemolysis, warm AIHA is diagnosed with a positive direct antiglobulin test (DAT) for IgG and spherocytes [2, 5, 7, 14]. Hemolysis is evaluated by a CBC exhibiting increased levels of lactate dehydrogenase, haptoglobin, bilirubin and reticulocyte count [14]. The presence of cold agglutinins rules out the diagnosis for warm AIHA. The diagnostic techniques for ITP and AIN are not as specific or sensitive, hence, diagnosis is often made via exclusion. Identifying antiplatelet antibodies have not been indicated as this lacks both specificity and sensitivity. The use of monoclonal antibody immobilization platelet assay (MAIPA) has been found to have higher specificity and sensitivity in the diagnosis of ITP [2]. Like antiplatelet antibodies, the presence of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCAs) have also been difficult to detect, hence the diagnosis of ITP is also done by exclusion in the absence of other thrombocytopenic pathologies [2].

In secondary ES, due to the lack of established guidelines, chest X-rays and abdominal computed tomography (CT) scans can be done to evaluate common underlying conditions such as SLE and ALPS [5]. More so, secondary ES has a poorer prognosis than primary. Underlying conditions must be promptly identified and treated to ensure decreased morbidity.

Treatment and management

First-line treatment of ES consists of corticosteroids and intravenous (IV) immunoglobulin. The second-line treatment for refractory ES involves the use of immunosuppressive drugs such as rituximab, a chimeric anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody [7]. The use of this results in the selective depletion of B cells in apoptosis via complement and antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity [3]. Splenectomy is an option in uncomplicated ITP. In severe and refractory cases, stem cell transplant gives potential for a long-term cure.

Literature review

The European Hematology Association in 2005 defined the spectrum of ES based on a retrospective analysis of 68 cases [8]. It was through the work of this group how researchers came to the conclusion that ES was associated with an autoimmune hematologic phenomenon and a state of immune dysfunction. This condition has been categorized into primary ES and hematologic immune abnormalities since its inception in 1951 by Robert Evans who posited a correlation with thrombocytopenia. Due to lack of workup and patient’s not being treated appropriately, risk stratification for thrombosis has not been well established [8]. Although the rate of thrombosis risk has been well-established in AIHA and ITP in the analysis of retrospective studies, this has not translated to a possible correlation in those with ES.

Recent research has demonstrated that ES is associated with AIHA 37% to 73% of the time [7]. This helps clinicians further narrow down appropriate treatment strategy of ES based on the likelihood of comorbidities such as the aforementioned present in patients. Due to the hematologic and immunologic link of ES, this condition predominates in children [7]. The pediatric patient population is especially vulnerable due to immune immaturity and the possible severe hematological sequelae especially if diagnosed during pregnancy. During hematological and immunological analysis, deficiency in the ratio of CD4/CD8 has been theorized as a possible cause for developing ES, but due to lack of evidence-based treatment, there is a rift of possible low-risk and effective clinical solutions available for mitigating the disease course. This creates a challenge for clinicians and physicians to create adaptive treatments that will slow disease progression or even possibly cure ES.

Conclusions

ES is diagnosed via exclusion. Although response to corticosteroids and IV immunoglobulins is quite successful, relapse to treatment is common. In such cases, immunosuppressants, such as rituximab, splenectomy and stem cell transplant can be considered. As such, patients presenting with ITP or warm AIHA, alongside proper treatment, should be followed closely to quickly diagnose any new onset autoimmune problems. More so, ES should be included in differentials in patients with symptoms of AIHA, ITP, cytopenias and recurrent infections. Due to the lack of specificity in most diagnostic techniques, further research pertaining to the expeditious diagnosis is required.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge our preceptor, Dr. Shahzad, who not only contributed significantly and oversaw our case, but also gave us the required imaging and data.

Financial Disclosure

There has been no financial support or funding that could have influenced our research in any way.

Conflict of Interest

Authors do not have any conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained verbally, twice, from our patient.

Author Contributions

All authors have provided critical feedback and helped shape the research. Jennie An conceived the idea of the case report/designed the scope of the study, majorly contributed to the writing of this manuscript, proofread and made extensive corrections/changes to the manuscript, obtained all data necessary for the manuscript, and organized the flow of the paper to fit the scope of the study. Preye Amaruntowa conceived the idea of the case report/designed the scope of the study, majorly contributed to the writing of this manuscript, proofread and made necessary corrections to the manuscript. Ali Khan conceived the idea of the case report/designed the scope of the study, majorly contributed to the writing of this manuscript, proofread and made necessary corrections to the manuscript, and helped obtain data necessary for the manuscript. Waleed Ahmed conceived the idea of the case report/designed the scope of the study, majorly contributed to the writing of this manuscript, proofread and made necessary corrections to the manuscript. Muhammad Shahzad MD supervised and oversaw the entire study, guaranteed the scientific integrity of the manuscript, conceived the idea of the case report/designed the scope of the study, and contributed to certain areas of writing in the manuscript.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Abbreviations

AIC: autoimmune cytopenia; AIHA: autoimmune hemolytic anemia; AIN: autoimmune neutropenia; ES: Evans syndrome; ITP: immune thrombocytopenia; IV: intravenous; NHL: non-Hodgkin lymphoma; SLE: systemic lupus erythematosus; SCT: stem cell transplantation

| References | ▴Top |

- Antoon JW, Metropulos D, Joyner BL, Jr. Evans syndrome secondary to common variable immune deficiency. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2016;38(3):243-245.

doi pubmed - Audia S, Grienay N, Mounier M, Michel M, Bonnotte B. Evans’ syndrome: from diagnosis to treatment. J Clin Med. 2020;9(12):3851.

doi pubmed pmc - Bhatnagar N, Kohli M, Fatima A. Evan’s syndrome - a case report. Hematol Int J. 2020;4(2):00074.

doi - Dhakal S, Neupane S, Mandal A, Parajuli SB, Sapkota S. Evans syndrome: a case report. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc. 2022;60(249):482-484.

doi pubmed pmc - Shaikh H, Mewawalla P. Evans syndrome. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

- Michel M, Chanet V, Dechartres A, Morin AS, Piette JC, Cirasino L, Emilia G, et al. The spectrum of Evans syndrome in adults: new insight into the disease based on the analysis of 68 cases. Blood. 2009;114(15):3167-3172.

doi pubmed - Jaime-Perez JC, Aguilar-Calderon PE, Salazar-Cavazos L, Gomez-Almaguer D. Evans syndrome: clinical perspectives, biological insights and treatment modalities. J Blood Med. 2018;9:171-184.

doi pubmed pmc - Otaibia ZD, Raob R, Sadashivb SK. A case of Evans syndrome: a clinical condition with under-recognized thrombotic risk. J Hematol. 2015;4:205-209.

doi - McCarthy MD, Fareeth AGM. Evans syndrome in a young man with rare autoimmune associations and transplanted liver. BMJ Case Rep. 2022;15(9):e251252.

doi pubmed pmc - Hansen DL, Moller S, Andersen K, Gaist D, Frederiksen H. Evans syndrome in adults - incidence, prevalence, and survival in a nationwide cohort. Am J Hematol. 2019;94(10):1081-1090.

doi pubmed - Lemos LA, Miranda DBD, Rosado MO. A rare case of Evans syndrome associated with optic neuritis: a case report. Open Access J Ophthalmology. 2023;8(1):1-5.

doi - Satarasinghe R, Jayawardana R, Wijesinghe R, Samarasinghe R, Dias K. A case report of Evan's syndrome preceding and masking the diagnosis of abdomino-pelvic tuberculosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:269.

doi - Savasan S, Warrier I, Ravindranath Y. The spectrum of Evans' syndrome. Arch Dis Child. 1997;77(3):245-248.

doi pubmed pmc - NORD. Evans syndrome. 2015. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/evans-syndrome/ (accessed: March 1, 2024).

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Hematology is published by Elmer Press Inc.