| Journal of Hematology, ISSN 1927-1212 print, 1927-1220 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Hematol and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://www.thejh.org |

Case Report

Volume 13, Number 1-2, April 2024, pages 29-33

Hepatosplenic Alpha-Beta T-Cell Lymphoma: A Challenging Diagnostic Entity

Abanoub Gabraa, c, Joanna Polancob, Shrija Thapab, Sumit Sawhneyb, Alexey Glazyrina

aDepartment of Pathology, HCA East Florida, Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA

bDepartment of Internal Medicine, HCA East Florida, Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA

cCorresponding Author: Abanoub Gabra, Department of Pathology, HCA East Florida, Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA

Manuscript submitted November 25, 2023, accepted February 8, 2024, published online April 9, 2024

Short title: Hepatosplenic Alpha-Beta T-Cell Lymphoma

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jh1203

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma (HSTCL) is rare and clinically very aggressive T-cell lymphoma. The majority of cases harbor γδ T-cell receptors (TCRs); however, in some even rarer cases, tumor cells harbor αβ TCR. Recent studies suggest that αβ cases may have distinct morphological characteristics and demonstrate an even more aggressive course. In this case report, we demonstrated that in line with previous findings, αβ case of HSTCL had hemolytic presentation, demonstrated a very aggressive clinical course, and was unrelated to immunosuppression. Morphologically, tumor cells demonstrated diffuse growth pattern, blastoid morphology, and were CD8+ positive on the background of CD4+ small to medium reactive T cells. Additionally, the liver tumor cells demonstrated periportal localization, and in bone marrow, evidence of emperipolesis was noted. The latter finding may significantly contribute to pancytopenia characteristic, all types of HSTCL. Those unusual morphologic and clinical characteristics make diagnosis of this rare subtype of rare disease very challenging. More case analysis is required to establish whether αβ/γδ HSTCL are prognostically or morphologically significantly distinct entities.

Keywords: Hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma; T-cell lymphoma; αβ T-cell lymphoma

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma (HSTCL) is a rare entity of clinically aggressive extranodal and systemic T-cell lymphoma involving the spleen, liver, and bone marrow [1]. This disease was first described in 1981 as a provisional entity: “γδ hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma”. After identifying rare cases with an αβ phenotype, the term “hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma” was first used in 1990 [2]. T cells are divided into αβ and γδ T cells based on the expression of their respective T-cell receptor (TCR). Less than 30 cases of αβ HSTCL were reported in the literature [3]. Earlier studies suggested that two subtypes of HSTCL (αβ and γδ) show similar clinicopathologic and cytogenetic features; however, αβ expression was associated with shorter patient survival [4], and most of the reported cases of γδ HSTCL are CD4-, CD8-, while most reported αβ cases are CD8+ with distinct “blastoid” morphology [3, 4]. Due to the paucity of reported cases, it is not clear whether αβ/γδ HSTCL is prognostically or morphologically significantly distinct entities [4]. We report here a case of αβ HSTC with the hemolytic presentation, very aggressive clinical course, and tumor cells expressing CD8+ with blastoid morphology as described for the majority of known αβ HSTC. We also describe some unique morphologic findings, including periportal instead of perisinusoidal hepatic malignant infiltration and evidence of bone marrow emperipolesis, which may significantly contribute to pancytopenia related to lymphoma experienced by all patients with HSTCL. To our knowledge, this is the first report of emperipolesis in HSTCL.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

A 46-year-old African American female presented with generalized weakness, shortness of breath, and abdominal distension for the past 2 months and recently developed worsening shortness of breath, fatigue, and jaundice. Her only medical pertinent medical history was heavy vaginal bleeding due to uterine fibroids and recent nitrofurantoin use due to a urinary tract infection 2 weeks ago. The patient denied any pertinent social history and was not under any regular medication. Upon presentation, she was febrile, dyspneic, and icteric. Her initial blood tests showed a hemoglobin of 5.6 g/dL, platelets 29 × 109/L, white blood cell (WBC) 17 × 109/L bilirubin total 3.3 mg/dL, indirect bilirubin 2.4 mg/dL, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 164 U/L, aspartate transferase (AST) 211 U/L, alkaline phosphate 288 U/L and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) of over 1,000. The glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) level and haptoglobin were within normal range. The rheumatoid factor was within normal range, and the antinuclear antibody was negative. Furthermore, computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis showed hepatosplenomegaly and fibroid uterus. She was promptly managed with blood transfusion, antibiotics, and intravenous fluids.

The patient was suspected of having non-immune hemolysis with a myelotoxic process given a negative Coombs test and markedly elevated LDH and leucoerythroblastic picture on the peripheral smear. Given rapid decline with increasing bilirubin, lymphoproliferative disorder was the clinical diagnosis; however, flow cytometry analysis on marrow was non-diagnostic as neoplastic T cells were not captured by flow cytometry.

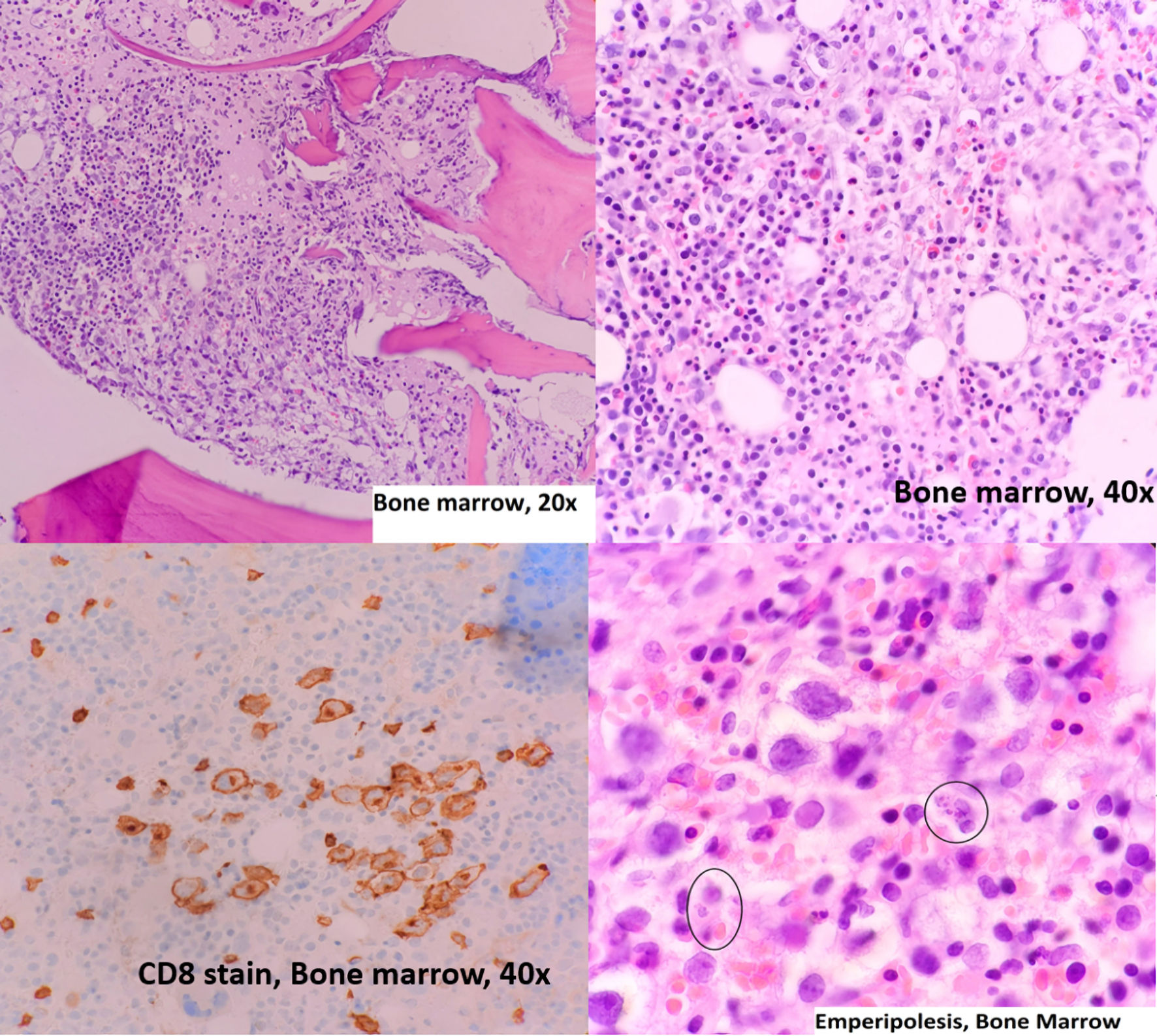

A hemolytic process was suspected initially, such as G6PD deficiency hemolytic anemia case due to the recorded high temperatures, jaundice, abdominal pain, and history of recent antibiotic use. Other disorders were also suspected, such as a hemoglobin disorder due to her ethnicity, even a myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), or underlying malignancy such as leukemia, as the patient became pancytopenic in a matter of days. Also, her initial extensive workup was negative, including hemoglobin electrophoresis, flow cytometry, MDS fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) panel, and lymphoma/leukemia panel. Peripheral blood did not demonstrate abnormal cells, and no reticulocytosis was noted. Eventually, the patient underwent a bone marrow biopsy. The bone marrow biopsy showed normal bone marrow replaced at 20-30% by sinusoidal and diffuse interstitial CD8+ neoplastic blastoid cells infiltration with emperipolesis on the background of small to medium CD3+, CD4+, CD5+ reactive lymphocyte infiltrate (Figs. 1, 2). Tumor cells were positive for CD3, CD2, CD7, T-cell receptor beta F1 (TCRBF1), T-cell intracytoplasmic antigen 1 (TIA1) and negative for CD5, TCRγ, CD4, S100, cyclinD1, pancytokeratin, CD30, CD21, CD23. CD56 highlighted a subset of cells. Trilineage hematopoiesis was preserved with no evidence of myelodysplasia or blasts proliferation. Significant erythroid hyperplasia was noted in preserved hematopoiesis (myeloid/erythroid ratio: about 0.3:1). Flow analysis was non-contributive, and an attempt to perform TCR analysis by flow was non-contributory. Cytogenetics analysis was negative for abnormalities.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Bone marrow aspiration, hematoxylin and eosin stain and immunohistochemistry. Circles mark the emperipolesis process. |

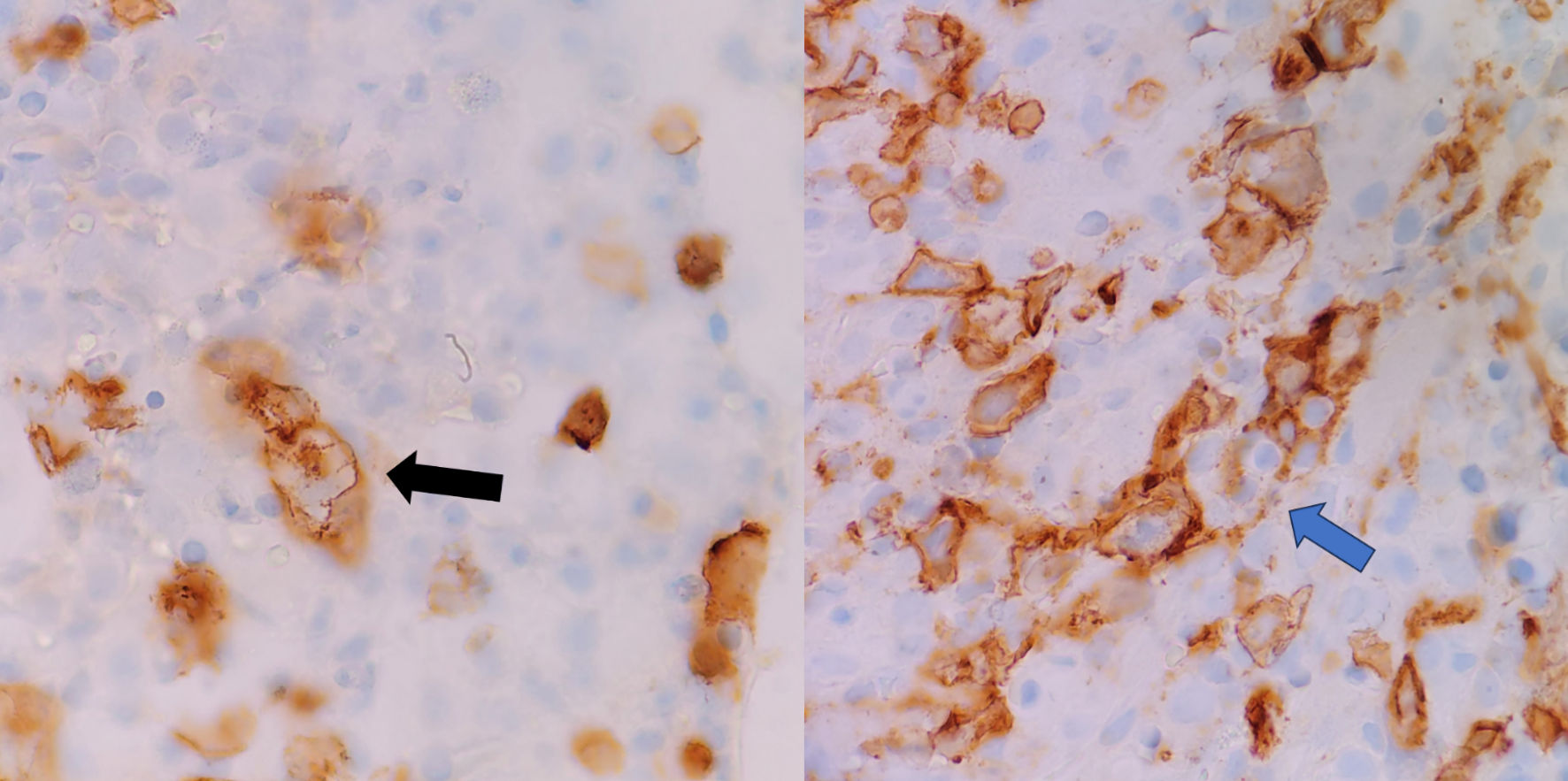

Click for large image | Figure 2. Emperipolesis. The blue arrow marks CD8 positive T cell engulfing erythroid precursors, and the black arrow marks cell membrane invaginations during emperipolesis. |

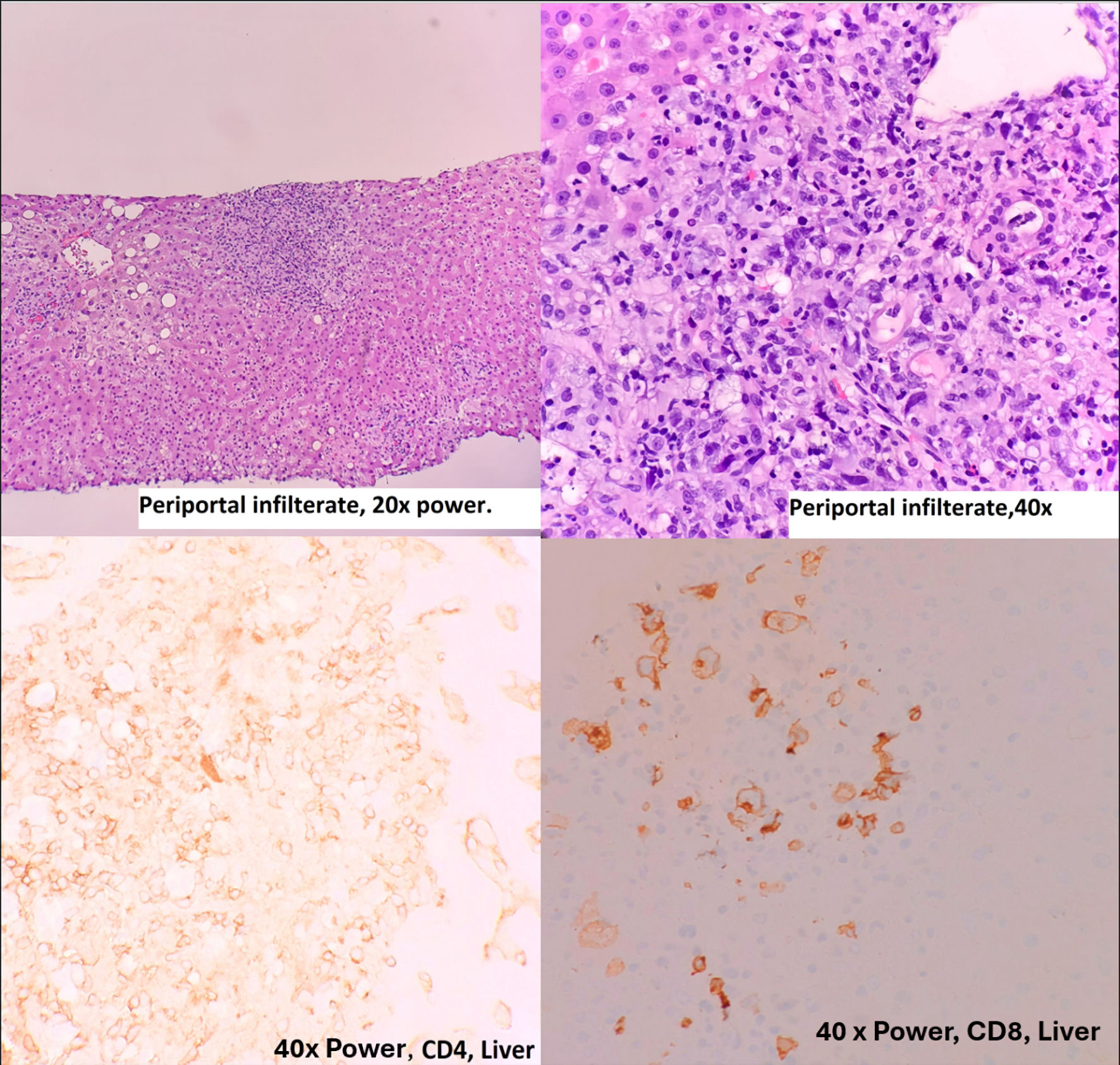

During the hospitalization, the patient developed heavy vaginal bleeding, and a hysterectomy was performed. Unfortunately, the patient had a complication of fluid overload postoperative and had to be intubated for a short period. During her sedation period, a liver biopsy was performed due to a decline in Karnofsky performance scale index, deteriorating hyperbilirubinemia leading to pigmented nephropathy, and worsening of other liver function tests. Liver biopsy showed periportal infiltration of CD8+ medium to large “blastoid” neoplastic cells in a background of small to medium CD3+, CD4+, and CD5+ lymphocyte infiltrate with morphology and immunophenotype similar to bone marrow, which can mimic reactive changes (Figs. 3, 4). The diagnosis was established in-house and confirmed through consulting a tertiary academic institution.

Click for large image | Figure 3. Liver biopsy, hematoxylin and eosin stain and immunohistochemistry. |

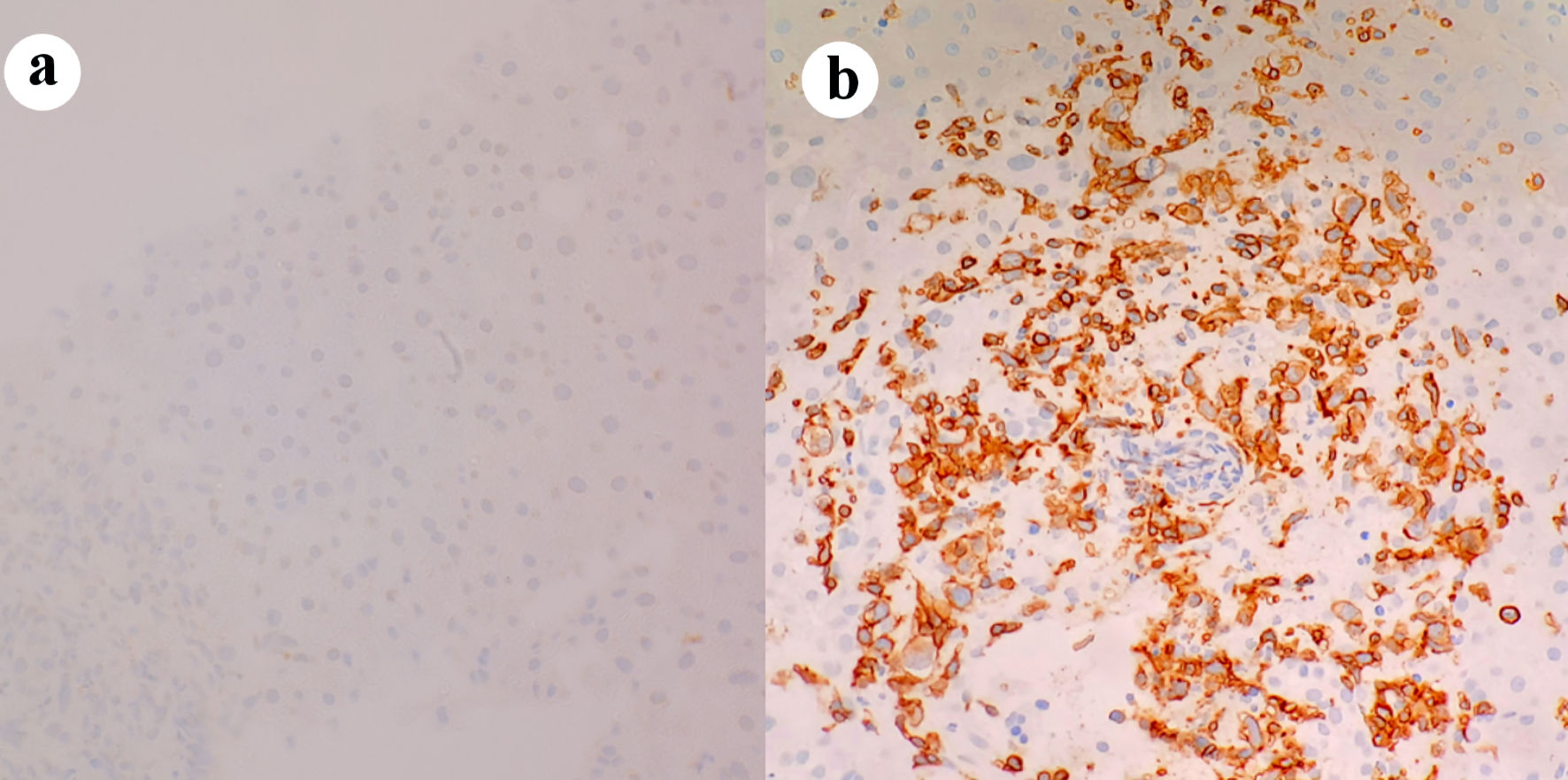

Click for large image | Figure 4. T-cell receptor immunohistochemical staining of periportal infiltrates showing negative γδ receptor in (a), positive αβ receptor in (b). |

Cyclophosphamide and carboplatin were offered as options with the concern of prolonged heme toxicity since the patient was facing end organ damage. Unfortunately, she developed an acute upper gastrointestinal bleed from a suspected stress ulcer, which led to further deterioration clinically and treatment delay. After an extended conversation with the patient and her family, the decision was made for palliative care.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

α/β T cells are T cells that harbor TCRα/β. Under normal conditions, only < 5% of circulating lymphocytes represent γδ T cells. However, they are commonly found in lymphoid organs, mucous membranes, the gastrointestinal tract, and spleen [2, 3]. Accordingly, the vast majority of HSTCL are γδ type. The exact mechanism behind the development of HSTCL is not well understood, but it has been suggested that prolonged exposure to antigens in individuals with immune deficiency or dysregulation could play a significant role. Approximately 20% of γδ HSTCL cases occur in patients with immune suppression [5, 6]. However, that seems inaccurate for the α/β type [3, 7]. Of note in the case presented was that there was no evidence of patient immunosuppression.

This case of αβ HSTCL illustrates some atypical features of this variant of HSTCL, which make diagnosis difficult, especially considering the extremely low incidence of the disease. Unlike most of the γδ cases, which usually demonstrate monomorphic CD4/CD8 negative small to medium-sized lymphocytes in the sinusoidal hepatic location [8], our case has shown periportal hepatic infiltration of blastoid CD8+ cells on the background small to medium reactive CD4+ T cells. Moreover, flow analysis was non-contributive and demonstrated only the same background CD4+ T cells, likely due to the fragility of large blastoid tumor cells. This makes diagnosis particularly challenging as it relies on tissue diagnosis and analysis of tissue sections. Pathologists should concentrate on CD8+ CD3+ blastoid tumor cells, ignoring background reactive CD4+ CD3+ T cells. Bone marrow infiltration was diffuse, not sinusoidal, as observed in more typical γδ HSTCL cases, findings also noted in previously described αβ cases [3].

Patients with HSTCL usually present with hepatosplenomegaly and B symptoms, i.e., fever, anorexia, weight loss, and night sweating. Both liver and spleen are diffusely enlarged with no lymphadenopathy [4]. Cytopenia, high LDH, and B2 micro-globin are common laboratory findings [4, 9]. In HSTCL, there is typically a mild to moderate increase in liver enzymes, indicating hepatocellular damage and necrosis. Thrombocytopenia, resulting from significant splenomegaly, is often the most notable feature in complete blood count (CBC) [6]. An interesting finding in this case report is bone marrow emperipolesis, which may significantly contribute to pancytopenia experienced by all HSTCL patients. A new treatment approach can be tested using medications suppressing emperipolesis if observed in other cases. This case was presented with hemolytic anemia, similar to the previously described case of αβ HSTCL [3].

So far, the largest series of αβ HSTCL failed to demonstrate significant clinicopathological and cytogenetic differences between αβ and γδ subtypes except for female predominance and older median age [4]. However, a growing body of evidence, including this case report, suggests that αβ cases demonstrate some clinical and morphological differences from more common γδ cases, including hemolytic presentation, more aggressive clinical course, CD8+ blastoid tumor cells with a diffuse pattern of growth [3].

In conclusion, this case report further supports the notion that αβ HSTCL may have different morphological and clinical features as compared to the more common γδ type. Those include blastoid CD8+ tumor cells rather than CD4, CD8- medium to small T cells (and, therefore, low sensitivity of flow analysis); diffuse bone marrow infiltration; no connection to immunosuppression; presentation with suspected hemolytic anemia; and an even more aggressive clinical course. Some additional features were noted (periportal liver tumor infiltration, emperipolesis). More cases are required to characterize those diseases as separate or similar entities.

Both types of HSTCL have very poor prognoses with a median survival of less than 1 year [6]. Due to the paucity of cases, no standard therapy exists with CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone)-like regimens offered to patients most often [3]. Further efforts are required to understand better the cause, pathophysiology, and therapeutic approaches to this rare, deadly disease. A high index of suspicion for HSTCL should be kept in rapidly deteriorating patients with hepatosplenomegaly caused by lymphoproliferative neoplasm with aberrant T-cell marker expression since early treatment could prolong survival. We agree that observed emperipolesis may not contribute to developing pancytopenia. However, this is a novel observation, and some contributions to pancytopenia, particularly anemia, cannot be ignored.

Acknowledgments

The research team acknowledges Dr Glazyrin for excellent resident mentoring and teaching.

Financial Disclosure

No funding was received for the research topic.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest related to the research topic.

Informed Consent

Informed consent is waived based on our institution’s guidelines.

Author Contributions

Dr. Glazyrin and Dr. Swehany: editing and reviewing. Dr. Gabra, Dr. Polanco, Dr. Thapa: data collection and article writing.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

| References | ▴Top |

- Vega F, Medeiros LJ, Gaulard P. Hepatosplenic and other gammadelta T-cell lymphomas. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;127(6):869-880.

doi pubmed - Gaulard P, Jaffe ES, Krenacs L, Macon WR. Hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma In: Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, eds., et al. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues, Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2017. p. 381-382.

- Ibrahim FA, Shanmugam V, Amer A, El-Omri H, Al-Sabbagh A, Taha RY, Soliman DS. An unusual case of hepatosplenic alphabeta T-cell lymphoma presenting with Coombs'-negative hemolytic anemia. Clin Med Insights Oncol. 2015;9:123-128.

doi pubmed pmc - Macon WR, Levy NB, Kurtin PJ, Salhany KE, Elkhalifa MY, Casey TT, Craig FE, et al. Hepatosplenic alphabeta T-cell lymphomas: a report of 14 cases and comparison with hepatosplenic gammadelta T-cell lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25(3):285-296.

doi pubmed - Jacobs MF, Anderson B, Opipari VP, Mody R. Hepatosplenic alphabeta T-cell lymphoma as second malignancy in young adult patient with previously undiagnosed ataxia-telangiectasia. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2020;42(6):e463-e465.

doi pubmed pmc - Roelandt PR, Maertens J, Vandenberghe P, Verslype C, Roskams T, Aerts R, Nevens F, et al. Hepatosplenic gammadelta T-cell lymphoma after liver transplantation: report of the first 2 cases and review of the literature. Liver Transpl. 2009;15(7):686-692.

doi pubmed - Nagai Y, Ikegame K, Mori M, Inoue D, Kimura T, Shimoji S, Togami K, et al. Hepatosplenic alphabeta T cell lymphoma. Int J Clin Oncol. 2010;15(2):215-219.

doi pubmed - Farcet JP, Gaulard P, Marolleau JP, Le Couedic JP, Henni T, Gourdin MF, Divine M, et al. Hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma: sinusal/sinusoidal localization of malignant cells expressing the T-cell receptor gamma delta. Blood. 1990;75(11):2213-2219.

pubmed - Yabe M, Miranda RN, Medeiros LJ. Hepatosplenic T-cell Lymphoma: a review of clinicopathologic features, pathogenesis, and prognostic factors. Hum Pathol. 2018;74:5-16.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Hematology is published by Elmer Press Inc.