| Journal of Hematology, ISSN 1927-1212 print, 1927-1220 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Hematol and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://www.thejh.org |

Case Report

Volume 13, Number 5, October 2024, pages 238-244

Primary Refractory Discordant Diffuse Large B-Cell and Classical Hodgkin Lymphoma

Yuxin Baia, d, Samantha Bolgera, d, Sahar Khana, b, Nikhil Sanglea, c, Luojun Wanga, c, Andrea L. Cervia, b, e

aSchulich School of Medicine and Dentistry, London, ON, Canada

bDepartment of Medical Oncology, Windsor Regional Cancer Center, ON, Canada

cDepartment of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, London Health Sciences Center, ON, Canada

dThese two authors contributed equally to this work.

eCorresponding Author: Andrea L. Cervi, Department of Medical Oncology, Windsor Regional Cancer Center, Windsor, ON N8W 1L9, Canada

Manuscript submitted June 12, 2024, accepted September 6, 2024, published online October 21, 2024

Short title: Primary Refractory Discordant DLBCL and cHL

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jh1303

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Discordant lymphomas are defined as two or more distinct pathological lymphomas occurring in the same patient. Due to the rarity of discordant lymphomas, which is due in large part to the difficulty in establishing the diagnosis, the literature is limited to small case series and case reports. Consequently, guidelines on therapeutic strategies are lacking. This article presented a case of primary refractory discordant large B-cell lymphoma and classic Hodgkin lymphoma in a young man based on cervical node and mediastinal mass biopsy, respectively. This case illustrates the difficulty in establishing the diagnosis, which ultimately warranted a high index of clinical suspicion and pursuit of multiple sequential biopsies, as well as a novel treatment strategy using an immune checkpoint inhibitor.

Keywords: Discordant lymphoma; Large B-cell lymphoma; Classical Hodgkin lymphoma; Checkpoint inhibitor

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Lymphomas represent a broad category of lymphoid malignancies that vary in clinical presentations and responses to treatment. Classification of lymphomas is based on cell lineage, morphology, immunophenotype, genetic, and molecular features [1]. Rarely, two or more distinct pathological types of lymphoma can occur in the same patient. Two concurrent lymphomas are diagnosed as composite lymphomas if occurring in a single tissue [2], or discordant lymphomas if existing in different anatomical locations [3]. One lymphoma type occurring after another in a single patient is diagnosed as sequential lymphoma [4]. The identification of sequential discordant lymphoma is challenging, as multiple separate sites of biopsy are required, which is not routinely performed due to rarity of this diagnosis and invasive nature of the diagnostic procedure. Moreover, treatment remains problematic owing to the lack of clinical guidelines. Data in the literature consist of small case series and case reports [4, 5].

The current report describes a young patient presenting with refractory, discordant diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and classical Hodgkin lymphoma (CHL) sequentially diagnosed in a cervical node and mediastinal mass biopsy, respectively. DLBCL is an aggressive neoplasm that arises from mature B lymphocytes, characterized by the large size of the cells and a diffuse architecture of growth [6]. CHL is an entity characterized by the presence, within an inflammatory background, of Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg (HRS) cells, which are also of B-cell origin, but are distinguished by a loss of B-cell gene expression, resulting in an incomplete expression of B-cell markers [7]. In general, CHL and DLBCL are two disease entities with differing clinical presentation and pathological features that require different treatment approaches. Diagnosis of discordant DLBCL and CHL in this patient required a high index of suspicion, followed by a novel choice of therapy.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

Investigations

The patient was a 22-year-old male presenting with symptoms of worsening neck pain, weight loss and drenching night sweats for 2 months. He was otherwise healthy, with no significant medical history. There was no family history of hematological malignancies or disease. The physical exam was positive for palpable adenopathy in anterior cervical lymph node chain bilaterally, including a large hard node over the suprasternal notch.

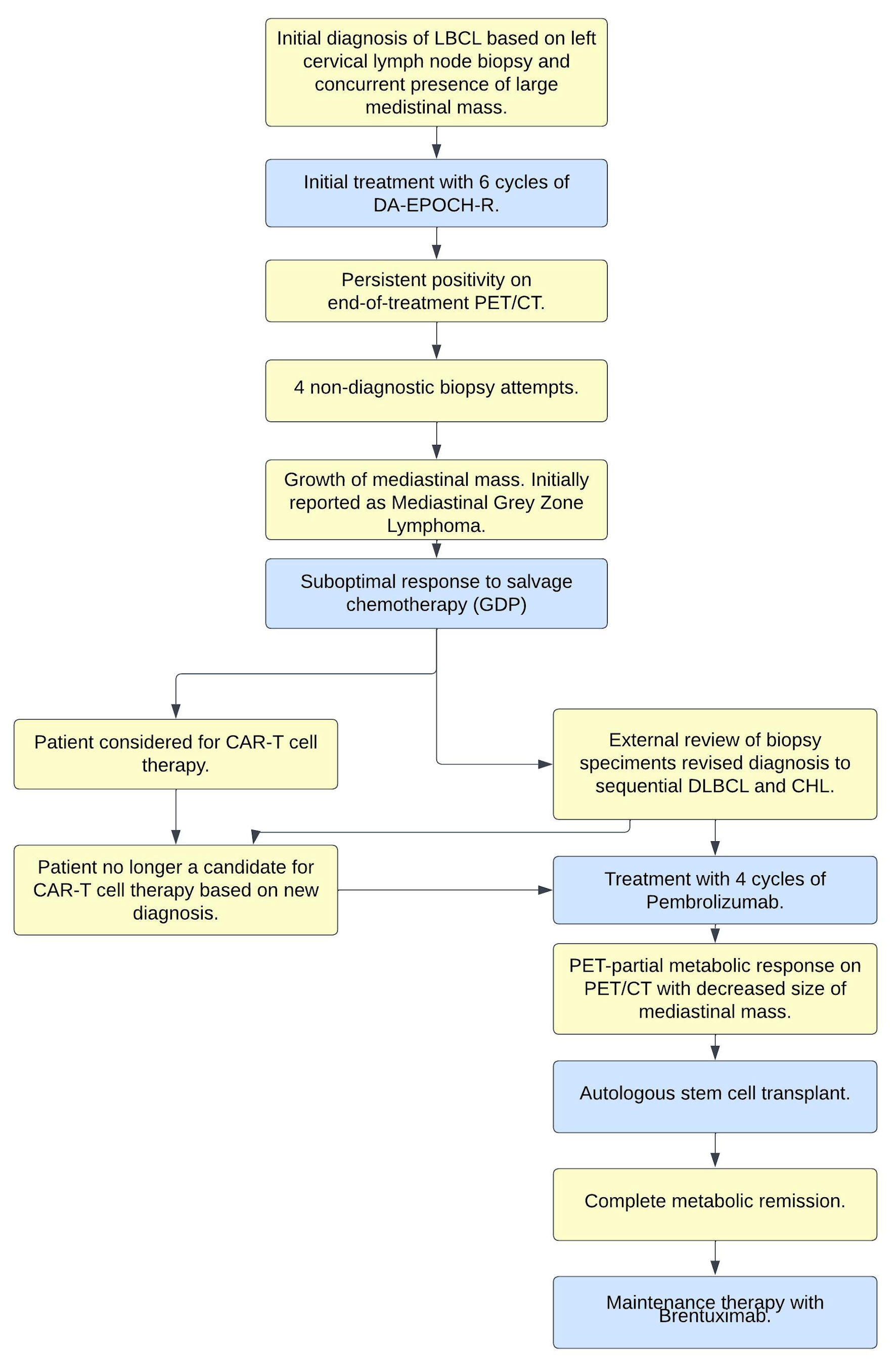

Computerized tomography (CT) imaging of the neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis confirmed the presence of neck adenopathy and identified a large mediastinal mass. He was found to have stage IVE disease with a pericardial effusion and a hypermetabolic anterior mediastinal mass measuring 22 cm craniocaudally on positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT). There was no clinical evidence of tamponade, and ejection fraction was preserved on baseline echocardiogram. A core needle biopsy of a left neck lymph node revealed an aggressive large B-cell lymphoma, query primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma (PMBL) versus DLBCL. Figure 1 provides a summary of the complete clinical course.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Clinical-pathologic summary of events. LBCL: large B-cell lymphoma; CHL: classical Hodgkin lymphoma; DA-EPOCH-R: dose-adjusted EPOCH-R; DLBCL: diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; PET/CT: positron emission tomography/computed tomography; EPOCH-R: etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and rituximab; GDP: gemcitabine, dexamethasone, cisplatin; CAR: chimeric antigen receptor. |

Treatment

The patient underwent urgent sperm banking, followed by initiation of dose-adjusted EPOCH-R (etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and rituximab) chemoimmunotherapy. After three cycles, interval restaging CT scans demonstrated a significant reduction in the size of the mediastinal mass and cervical adenopathy. He completed six cycles total of dose-adjusted EPOCH-R, having achieved dose escalation 5, without significant complications.

An end of the treatment, PET/CT scan demonstrated persistent disease with ongoing hypermetabolic areas in the anterior mediastinum and bilateral parasternal lymph nodes, consistent with Deauville 4 disease, although there was overall improvement in size and metabolic activity compared to baseline imaging. As the patient was clinically asymptomatic, a decision was made to repeat the PET/CT in 8 weeks, at which point there was evidence of progression in metabolic activity (Deauville 5) in the mediastinum. However, the patient had coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection at the time of this assessment; consequently, he underwent repeat PET/CT 6 weeks later, which demonstrated persistent Deauville 5 activity and an increase in size of the right supraclavicular lymph node, and increased size as well as increased F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) avidity in bilateral internal mammary lymph nodes, with new uptake in a mediastinal lymph node.

The patient was clinically asymptomatic throughout the course of these serial scans and had in fact returned to his employment full time. Serial biopsies were undertaken, including: a core biopsy of a right cervical lymph node, which was non-diagnostic and showed scanty fragments of muscle and soft tissue; a core biopsy of a right supraclavicular lymph node, which was non-diagnostic and did not identify any lymph node tissue; a right subclavicular excisional node biopsy, which showed mostly fibrofatty tissue with scattered small foci of benign lymphoid tissue; and finally, an excisional biopsy of the mediastinal mass, which showed thymic tissue with nodular necrotic areas compatible with post-therapy change and no definite viable residual lymphoma. As well, the patient’s case was reviewed at the local institution’s multidisciplinary case conference; he also underwent an external consultation at a tertiary care academic center with lymphoma expertise, with the recommendation to continually monitor for symptoms of disease; however, no further treatment was advised.

Follow-up and outcomes

Thirteen months after completion of his last cycle of dose-adjusted EPOCH-R, the patient reported pain over his proximal sternum, radiating into his right shoulder and arm, with an occasionally palpable lump. An urgent CT chest was done and revealed growth of the mediastinal mass, at which point a CT-guided biopsy of this mediastinal mass was undertaken and reported initially consistent with mediastinal grey zone lymphoma (mGZL). At this time, the patient was started on salvage chemotherapy in the form of GDP (gemcitabine, dexamethasone, cisplatin), and considered for autologous stem cell transplantation.

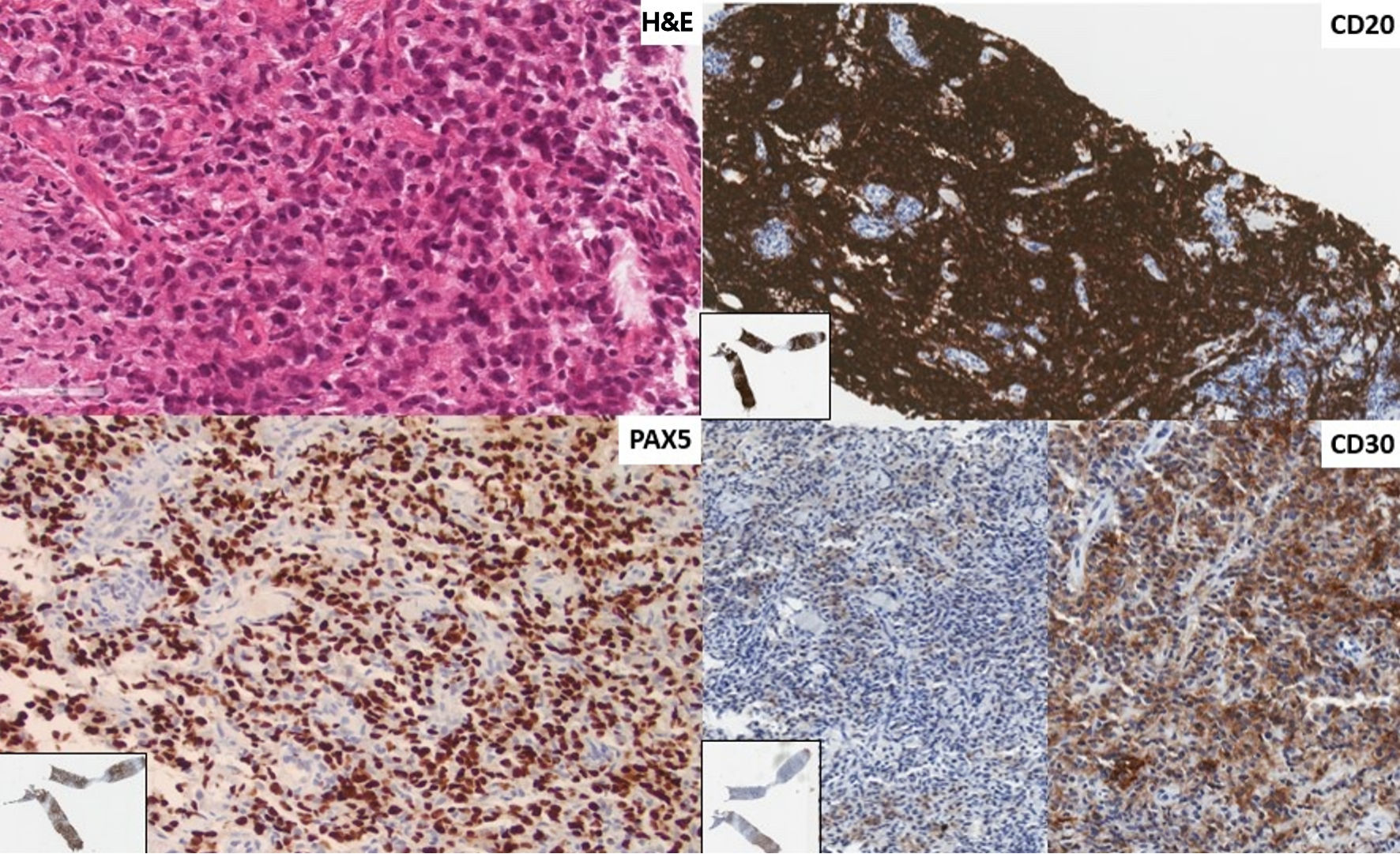

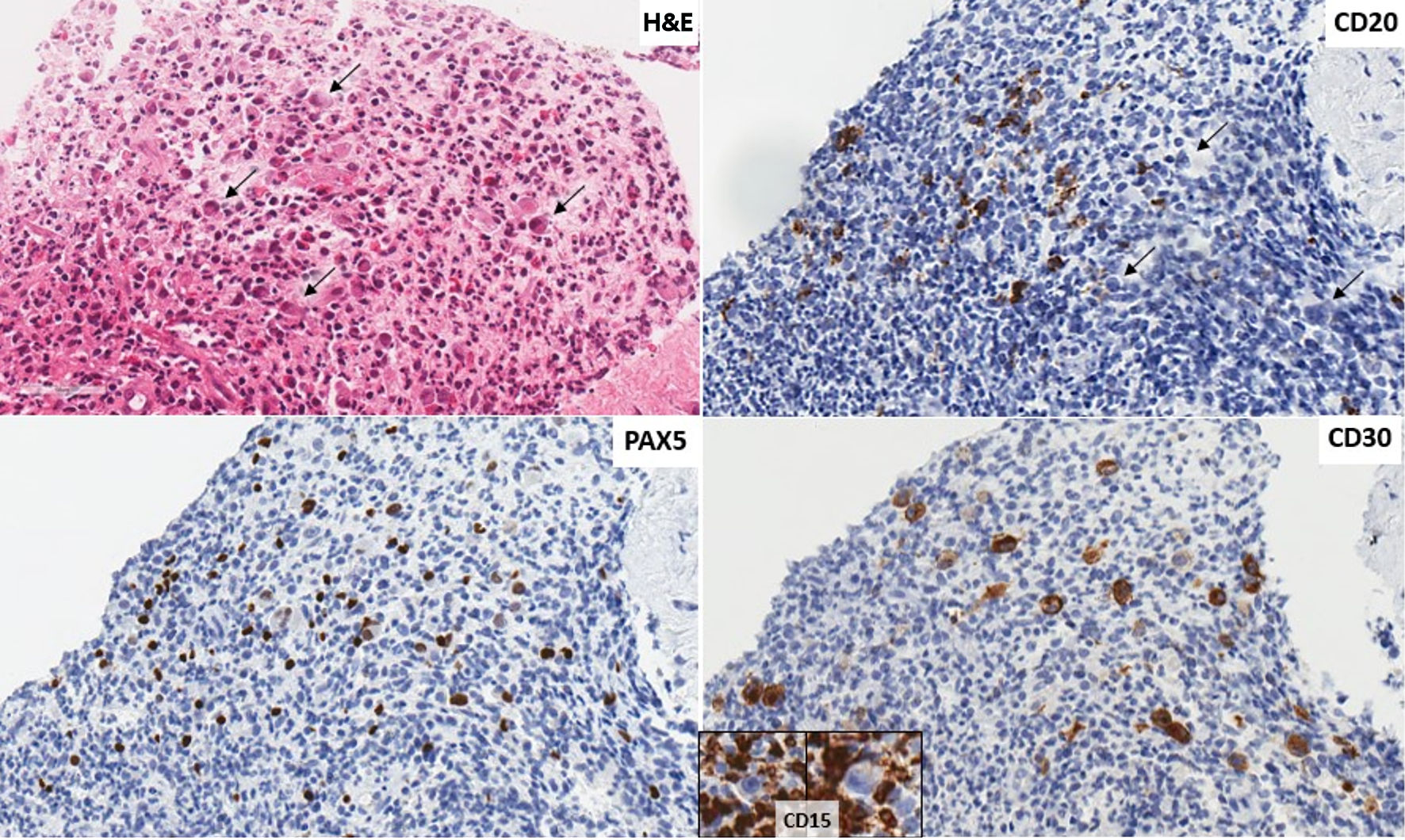

Following two cycles of GDP, a PET/CT scan demonstrated minimal improvement in hypermetabolic activity at the site of the mediastinal mass (Deauville 5b to Deauville 5a) and was overall consistent with a suboptimal response. At this juncture, the patient’s pathology specimens were sent to an academic tertiary care center for external review. The diagnosis of the first left neck lymph node (Fig. 2) was confirmed to be DLBCL, not otherwise specified (NOS), and the second mediastinal mass was revised as being consistent with involvement by CHL (Fig. 3). Tumor cells expressed programmed death ligand-1 (PD-L1) in both biopsies.

Click for large image | Figure 2. First instance of lymphoma shown in a biopsy of a left neck lymph node. The revised diagnosis is of a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of germinal center phenotype (CD10-, BCL6+, MUM1-). The architecture of the lymph node parenchyma is effaced by sheets of large rounded lymphoid cells (H&E stain × 400). There is diffuse immunoreactivity for CD20 and PAX5, and patchy staining for CD30 (× 200, insert: low power). There was no positivity for CD15 or CD23. Tumor cells are PDL1+. H&E: hematoxylin and eosin; PDL1: programmed death ligand-1; BCL6: B-cell lymphoma 6; MUM1: multiple myeloma 1; PAX5: paired box 5. |

Click for large image | Figure 3. Second instance of lymphoma shown in a biopsy of a mediastinal mass. The revised diagnosis is of a classic Hodgkin lymphoma. There are scattered large cells with Reed Sternberg and Hodgkin morphology (arrows) scattered in an eosinophil rich mixed lymphoid background (H&E stain, × 400). Tumor cells (arrows) that do not show immunoreactivity for CD20 (× 400), are positive for PAX5 (× 400), CD30 (× 400) and negative for CD15 (insert, background inflammatory cells positive). Tumor cells are PDL1+. H&E: hematoxylin and eosin; PDL1: programmed death ligand-1; PAX5: paired box 5. |

Prior to receiving the revised diagnosis, the patient had undergone six rounds of dose-adjusted EPOCH-R and two cycles of GDP salvage chemotherapy with suboptimal response and was being evaluated for chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy. However, an alternate therapeutic strategy was undertaken upon receipt of the updated diagnosis, given that chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy is not approved in this setting. Therefore, the patient’s therapeutic course was modified and instead a compassionate access to pembrolizumab, a programmed cell death (PD-1) blocking immune checkpoint inhibitor, was requested.

Following four cycles of pembrolizumab, a repeat PET/CT scan demonstrated a PET-partial response; consequently, the patient underwent autologous stem cell transplant, followed by maintenance brentuximab. The patient tolerated this treatment well. He remains in a complete metabolic response by PET/CT.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

The above case illustrates a young man initially diagnosed with aggressive B-cell lymphoma on biopsy of cervical lymph node, thought to possibly be PMBL due to the presence of concurrent mediastinal mass, whose inadequate response to typical therapy prompted further investigation and eventually led to a diagnosis of CHL on biopsy of mediastinal mass. Current management of advanced stage CHL involves multimodal systemic therapy using a combination of doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine and dacarbazine (ABVD). Given the unusual clinical course in this patient and use of a novel treatment strategy, this case presents a number of interesting learning points.

Lymphoproliferative disorders in the mediastinum arising from a B cell may be CHL, PMBL, mGZL, or DLBCL [8]. PMBL is a specific subtype of large B-cell lymphoma that is characterized by the infiltration of diffuse proliferation of large cells with clear cytoplasm and occasional HRS-like cells [9]. It expresses pan B-cell markers, but is distinguished from DLBCL with CD30, CD23 and MAL positivity [10-12]. Although CHL can also be of thymic B-cell origin, it has several distinct pathological features. CHL is diagnosed by the pathognomonic HRS cells in a particular inflammatory background of immune cells [13]. It has a downregulated B-cell program, with often negative CD79a, weak CD20 expression, and often absent BOB.1 and Oct-2 [13]. Cases of overlapping morphological and phenotypic features of PMBL and CHL are categorized as mGZL. mGZL exists on a continuum, where some cases have a CHL-like morphology versus PMBL immunophenotypes, or vice versa [13, 14]. On the genetic level, CHL, mGZL, and PMBL share abnormalities in the REL oncogene, JAK2, and programmed-death ligand genes PD1L1 and PD1L2 [12]. Furthermore, gene expression profiling suggests significant overlap in genes that were highly expressed in PMBL and CHL [15]. Throughout the patient’s clinical course, DLBCL, PMBL, mGZL, and CHL were all considered, reflecting the biological overlap between these lymphoma types.

The distinction between composite and sequential lymphomas is not always clear in clinical practice [16]. Early sequential lymphomas may be hidden composite lymphomas, with the second component only discovered after treatment failure. As previously reported in a retrospective case series, the low incidence of composite lymphomas may be underestimated among refractory and early relapsing patients, for whom a second biopsy is rarely performed [5]. In the current case, the patient initially presented with concurrent mediastinal disease with neck adenopathy but did not undergo further biopsies until he had persistent disease despite treatment. It is thus unknown if the mediastinal mass at the initial presentation already contained CHL. The serial PET imaging and non-diagnostic biopsies underscore the high degree of clinical suspicion required to pinpoint the diagnosis. In retrospect, two clues throughout the patient’s disease course suggested that his case was disparate from his initial diagnosis of diffuse large B cell lymphoma or primary mediastinal B cell lymphoma: 1) persistent PET-positive disease after dose-adjusted EPOCH-R therapy, which is typically associated with an overall response rate of 92% [17, 18]; and 2) the patient was clinically asymptomatic for nearly 1 year despite the radiographic presence of persistent disease, which is more in keeping with CHL than persistent aggressive B cell lymphoma [19, 20].

When two lymphoma types are present in the same patient, the therapeutic strategy needs to consider both disease components and is generally geared towards the more aggressive lymphoma subtype [3, 21]. Discovery of the coexisting CHL pathology was crucial for the treatment of this patient, as he was being considered for CAR T-cell therapy following suboptimal response to conventional salvage chemotherapy in the form of GDP. However, CAR T-cell therapy is not currently approved for Hodgkin lymphoma; consequently, this course of action would have predisposed the patient toward undue risk without disease control [22].

Patients with composite DLBCL and CHL reported in the literature have been treated most frequently using a DLBCL-like therapy, consisting of R-CHOP (rituximab, doxorubicin, methylprednisolone, cyclophosphamide, vincristine), or its modified successor, dose-adjusted EPOCH-R, as used in this case [16, 23, 24]. A few cases are reported to be treated with CHL-like therapy with ABVD or escalated BEACOPP (methylprednisolone, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, procarbazine, etoposide, bleomycin, vincristine) depending on the stage of disease [16]. One patient was treated with R-CHOP followed by R-ABVD, after discovering the CHL component in a second biopsy [5]. In most of the recently reported cases, patients achieved complete response after one chemotherapy regimen or after salvage therapy followed by autologous stem cell transplant [5].

Pembrolizumab is a monoclonal antibody that targets PD-1 receptors and blocks immune-suppressing ligands (PD-L1/2) to reactivate immune responses against tumor cells [25]. Using this immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy has been shown to be safe and effective in the treatment of relapsed or refractory (r/r) CHL, which is known to overexpress PD-L as a way to escape immune surveillance [26]. Consequently, pembrolizumab was approved in 2017 by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and Health Canada for r/r CHL [27]. In a multicohort phase 1b study, the therapeutic benefit of PD-1 blockade is more variable in non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), with overall response rate 48%, 12%, and 50% for r/r PMBL, DLBCL, and “other” NHL, respectively [28]. The patient’s refractory disease was primarily located in the mediastinum and consistent with CHL, making pembrolizumab a reasonable choice of therapy. This represents the first case of discordant lymphoma treated with an immune checkpoint inhibitor, pembrolizumab, with a favorable overall outcome. Although this is a single case study with limited duration of follow-up, it highlights a novel treatment strategy that warrants further research.

Learning points

This case underscores the importance of maintaining a high index of clinical suspicion for discordant lymphomas in cases of refractory or early relapsed lymphoma. Moreover, establishing the diagnosis of lymphoma rests on close collaboration with colleagues subspecialized in hematopathology, particularly in instances of an atypical clinical course. Finally, this experience suggests that pembrolizumab may be an effective treatment to consider for relapsing/refractory composite or discordant DLBCL and CHL.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the patient for providing us with consent to publish this case.

Financial Disclosure

This project was not funded.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest to declare.

Informed Consent

Written informed consent from this patient was obtained.

Author Contributions

AC and SK were involved with the patient’s care and conceptualized the case report. YB and SB performed the literature review, reviewed the patient chart, and drafted the manuscript. LW and NS provided biopsy images and hematopathology expertise. AC and LW revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the latest edition of the manuscript.

Data Availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

HL: Hodgkin lymphoma; NHL: non-Hodgkin lymphoma; CHL: classical Hodgkin lymphoma; DLBCL: diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; mGZL: mediastinal grey zone lymphoma; PET/CT: positron emission tomography/computed tomography; EPOCH-R: etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and rituximab; FDG: F-fluorodeoxyglucose; PD: programmed cell death; GDP: gemcitabine, dexamethasone, cisplatin; PMBL: primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma; ACVBP: doxorubicin, methylprednisolone, cyclophosphamide, bleomycin, vindesine; R-CHOP: rituximab, doxorubicin, methylprednisolone, cyclophosphamide, vincristine; ABVD: doxorubicin, vinblastine, bleomycin, dacarbazine; BEACOPP: methylprednisolone, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, procarbazine, etoposide, bleomycin, vincristine; CAR: chimeric antigen receptor

| References | ▴Top |

- Alaggio R, Amador C, Anagnostopoulos I, Attygalle AD, Araujo IBO, Berti E, Bhagat G, et al. The 5th edition of the World Health Organization Classification of haematolymphoid tumours: lymphoid neoplasms. Leukemia. 2022;36(7):1720-1748.

doi pubmed pmc - Kim H. Composite lymphoma and related disorders. Am J Clin Pathol. 1993;99(4):445-451.

doi pubmed - Mead GM, Kushlan P, O'Neil M, Burke JS, Rosenberg SA. Clinical aspects of non-Hodgkin's lymphomas presenting with discordant histologic subtypes. Cancer. 1983;52(8):1496-1501.

doi pubmed - Zarate-Osorno A, Medeiros LJ, Kingma DW, Longo DL, Jaffe ES. Hodgkin's disease following non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. A clinicopathologic and immunophenotypic study of nine cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1993;17(2):123-132.

pubmed - Aussedat G, Traverse-Glehen A, Stamatoullas A, Molina T, Safar V, Laurent C, Michot JM, et al. Composite and sequential lymphoma between classical Hodgkin lymphoma and primary mediastinal lymphoma/diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, a clinico-pathological series of 25 cases. Br J Haematol. 2020;189(2):244-256.

doi pubmed - Sehn LH, Salles G. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(9):842-858.

doi pubmed pmc - Wang HW, Balakrishna JP, Pittaluga S, Jaffe ES. Diagnosis of Hodgkin lymphoma in the modern era. Br J Haematol. 2019;184(1):45-59.

doi pubmed pmc - Pina-Oviedo S. Mediastinal Lymphoproliferative Disorders. Adv Anat Pathol. 2021;28(5):307-334.

doi pubmed - Satou A, Takahara T, Nakamura S. An update on the pathology and molecular features of Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(11):2647.

doi pubmed pmc - Rosenwald A, Wright G, Leroy K, Yu X, Gaulard P, Gascoyne RD, Chan WC, et al. Molecular diagnosis of primary mediastinal B cell lymphoma identifies a clinically favorable subgroup of diffuse large B cell lymphoma related to Hodgkin lymphoma. J Exp Med. 2003;198(6):851-862.

doi pubmed pmc - Pileri SA, Zinzani PL, Gaidano G, Falini B, Gaulard P, Zucca E, Sabattini E, et al. Pathobiology of primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2003;44(Suppl 3):S21-26.

doi pubmed - Steidl C, Gascoyne RD. The molecular pathogenesis of primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2011;118(10):2659-2669.

doi pubmed - Bosch-Schips J, Granai M, Quintanilla-Martinez L, Fend F. The grey zones of classic Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(3):742.

doi pubmed pmc - Traverse-Glehen A, Pittaluga S, Gaulard P, Sorbara L, Alonso MA, Raffeld M, Jaffe ES. Mediastinal gray zone lymphoma: the missing link between classic Hodgkin's lymphoma and mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29(11):1411-1421.

doi pubmed - Pittaluga S, Nicolae A, Wright GW, Melani C, Roschewski M, Steinberg S, Huang D, et al. Gene expression profiling of mediastinal gray zone lymphoma and its relationship to primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma and classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood Cancer Discov. 2020;1(2):155-161.

doi pubmed pmc - Trecourt A, Donzel M, Fontaine J, Ghesquieres H, Jallade L, Antherieu G, Laurent C, et al. Plasticity in classical Hodgkin composite lymphomas: a systematic review. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(22):5695.

doi pubmed pmc - Dunleavy K, Pittaluga S, Maeda LS, Advani R, Chen CC, Hessler J, Steinberg SM, et al. Dose-adjusted EPOCH-rituximab therapy in primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(15):1408-1416.

doi pubmed pmc - Shah NN, Szabo A, Huntington SF, Epperla N, Reddy N, Ganguly S, Vose J, et al. R-CHOP versus dose-adjusted R-EPOCH in frontline management of primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma: a multi-centre analysis. Br J Haematol. 2018;180(4):534-544.

doi pubmed - Dunleavy K, Wilson WH. Primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma and mediastinal gray zone lymphoma: do they require a unique therapeutic approach? Blood. 2015;125(1):33-39.

doi pubmed pmc - Shimabukuro-Vornhagen A, Haverkamp H, Engert A, Balleisen L, Majunke P, Heil G, Eich HT, et al. Lymphocyte-rich classical Hodgkin's lymphoma: clinical presentation and treatment outcome in 100 patients treated within German Hodgkin's Study Group trials. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(24):5739-5745.

doi pubmed - Kuppers R, Duhrsen U, Hansmann ML. Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of composite lymphomas. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(10):e435-446.

doi pubmed - Villeneuve PJA, Bredeson C. CAR-T cells in Canada; Perspective on how to ensure we get our value's worth. Curr Oncol. 2023;30(4):4033-4040.

doi pubmed pmc - Goyal G, Nguyen AH, Kendric K, Caponetti GC. Composite lymphoma with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and classical Hodgkin lymphoma components: a case report and review of the literature. Pathol Res Pract. 2016;212(12):1179-1190.

doi pubmed - Khan U, Hadid T, Ibrar W, Sano D, Al-Katib A. Composite lymphoma: opposite ends of spectrum meet. J Clin Med Res. 2017;9(3):213-215.

doi pubmed pmc - Hossain MF, Kharel M, Akter M, Parajuli B, Yadav I, Mandal N, Mandal A, et al. Effectiveness and safety of pembrolizumab in recurrent and relapsed classic Hodgkin lymphoma: a systematic review. Cureus. 2023;15(9):e46032.

doi pubmed pmc - Armand P, Rodig S, Melnichenko V, Thieblemont C, Bouabdallah K, Tumyan G, Ozcan M, et al. Pembrolizumab in relapsed or refractory primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(34):3291-3299.

doi pubmed pmc - Pembrolizumab approved for Hodgkin lymphoma - NCI. https://www.cancer.gov/news-events/cancer-currents-blog/2017/fda-pembrolizumab-hodgkin-lymphoma.2017. Accessed Mar 16, 2024.

- Kuruvilla J, Armand P, Hamadani M, Kline J, Moskowitz CH, Avigan D, Brody JD, et al. Pembrolizumab for patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma: phase 1b KEYNOTE-013 study. Leuk Lymphoma. 2023;64(1):130-139.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Hematology is published by Elmer Press Inc.